Harmonie Toros from the University of Kent published a paper about engaging with terrorism. According to her, a “key objection raised by terrorism scholars and policymakers against engaging in negotiations with terrorists is that it legitimizes terrorist groups, their goals and their means. Talking to them would serve only to incite more violence and weaken the fabric of democratic states, they argue.” In fact, many politicians advocate a policy of not negotiating with terrorists. This often has its roots in the belief that terrorists are not actually willing to accept compromise, a notion that undeniably applies to numerous terrorist groups, namely the ones with maximalist demands, e.g. ideological demands over beliefs or values.

|

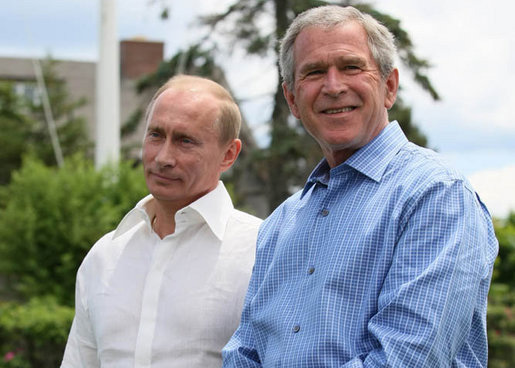

| George W. Bush & Valdimir Putin. Picture: White House |

If it is true that negotiations with terrorists encourage them to commit even more attacks, diplomacy would be a poor strategy for policymakers. As terrorism studies are ultimately aimed at finding ways to respond to and counter terrorism, scholars and dedicated citicens (like you) would have to discourage politicians from engaging in negotiations with terrorists. This would have a major impact on ongoing negotiations and peace processes. It is, therefore, important to test the assumption to give fact-based advice to policymakers and to effectively support their fight against violence.

One argument against the claim that negotiating with terrorists encourages more terrorism is that, in fact, many governments do (openly or secretly) negotiate with organizations they label “terrorist”. This holds even for governments that publicly pronounce against such actions. According to Peter R. Neumann from London's King's College, “[w]hen it comes to negotiating with terrorists, there is a clear disconnect between what governments profess and what they actually do.” For him it is not the question if, but how to engage in negotiations with terrorists “in a way that minimizes the risk of setting dangerous precedents and destabilizing its political system.” If governments find the right strategy to engage in negotiations with terrorists, they have a chance to end terrorism or at least reduce violence; the British government’s negotiations with the IRA are a successful example.

In a TEDx Talk at the Columbia School of International and Public Affairs, Mitchell Reiss from the US State Department warns that not negotiating might mean to miss an opportunity to end the

killing and violence but also points out the long and difficult road to successful negotiations. Another

| |||||||

| Gilad Shalit arriving at IDF airbase. Picture: IDF |

determination to adopt the hardline approach is only likely to reduce their options” (p. 73). A further argument for negotiations is the case of kidnapping or prisoner exchange. Even governments with rather strict policies towards terrorists agree at least sometimes to negotiate terms for a release of hostages to safe the lifes of their citizens. The prisoner exchange between Israel and the Hamas that freed IDF soldier Gilad Shalit is a famous example. It was widly and controversially disussed in the Israeli public. Some complained that the price was too high, others argued that terrorists should not be released at all and yet others were worried that negotiating with terrorists about hostage-release and the exchange of prisoners might incentivice further terrorist attacks. This claim would impicate that we should consider the kidnapping of Gilad Shalit and possible similar future events as acts of terrorism. This is problematic in many ways. Firstly, the status of the Hamas as a terrorist organization is internationally disputed. Furthermore, it is, after all, a democratically elected government. A discussion of the issue of state-terrorism would lead too far from our topic though. Secondly, in my opinion only one of the three requirements of my understanding of the term terrorism applies, namely the use of physical violence. I find the evidence for an attempt to spread fear not very compelling, especially since the Hamas demanded a ransom. I would, therefore, say that kidnapping-for-ransom does not constitute terrorism, particularly in cases in which the hostages are released. As a consequence, negotiations with terrorist groups about hostage release do not encourage more terrorism. The question if or if not they encourage kidnapping is a different one. At least in the case of Israel and the Hamas there haven't been any further incidences.

An argument that speaks for the claim that negotiating with terrorists encourages more terrorism is historical: Even though Nazi Germany was not a terror organization per definition, it can still serve as

|

| British Prime Minister Chamberlain announcing "Peace in our Time” |

Terrorism is oftentimes rooted in a major grievance that - at least sometimes - has to do with the way a government governs - or miscoverns. If the policymakers of a country don't want to negotiate with terrorists, they should at least consider weaker forms of engagement as it might help them to understand the grievance and find ways to tackle it. In the ideal (but admittedly rare) case, this could make a terrorist organization obsolete by destroying its basis.

Negotiating with terrorists might have negative consequences, but I strongly believe that there are cases in which the benefits outweigh the costs. It is always important to ask if an engagement can be fruitful, especially when dealing with groups holding maximalist demands. On the one hand it is easy to see how negotiations with for example a terrorist group promoting international jihad would be absolutely futile. This is because many groups holding maximalist demands do not even seek negotiations as they do not believe that a government would accept their conditions. Moreover, their objectives are completely opposed to the values of many societies and, therefore, disqualified as a basis of negotiatons. On the other hand there are cases in which negotiations might be a very helpful way to end political violence. Terrorist groups with limited demands like for example over territory are more likely to enter into negotiations and to actually agree to a compromise.

I believe that we cannot generalze on this issue. The assumption that negotiating with terrorists encourages even more terrorism is not completely wrong but also only partly true, depending on the type of group, e.g. if it holds limited or maximalist objectives, and the way the government is approaching negotiations. Negotiations with terrorist groups should, therefore, always be regarded as a tool of policymakers.

I think it's also important to add that terrorism, or the use of terror/violence deliberately committed on non-strategic/military objectives, is a MEANS, not an end, of achieving one's goals. As you mentioned, this means is typically used when a repressed group perceives that it has exhausted all peaceful means to convince a government to see things its way (e.g. the formation of the Moro National Liberation front in the Philippines in the 1970s when Muslim groups had their backs to the wall against a repressive Christian government). This means that not all freedom fighters/guerillas are terrorists (i.e. they may only target legitimate military targets).

ReplyDeleteThe term terrorism is itself easy prey to politicization and its exploitation for propaganda purposes. From a modern Western perspective, it is very easy to classify "obvious" groups as terrorist in nature e.g. Al-Qaeda, Al-Shabab, Abu Sayyaf, Boston Marathon bombers, etc. Not so for certain segments of say Muslim society who view Hamas, Hezbollah, Jabhat al-Nusra, etc as freedom fighters wanting to rid their societies of Western influence and Israeli occupation. The same arguments can be made for various secessionist groups across the world.

Further complicating the issue is the fact that there is no international consensus on the definition of terrorism since as mentioned it is a highly sensitive and political term, with definitions varying from country to country. It's for these reasons that I believe conceptualizing terrorism as a means, and not a goal in itself, is the most objective way of looking at it. However, making the argument that terrorism is a means problematic are so-called "random acts of violence." Cases in points are those random attacks across the US by individuals with apparently no political motivation behind their atrocities.